Heterodoxy Towards Moderation: Being Normal By Letting People Be Weird

We’re deep in the weeds of arguing about what needs to be done for Democrats to win the presidency again, but we still have extremely minimal data on what actually happened. I’m not yet in a place where I want to argue about shifts in particular demographic groups, when the big story is uniform swing and the estimates of vote share in demographics are all drawn from not-very-good exit polls.

Instead of torturing some data to try and do that, here are more general thoughts on what it means to “moderate” as a party, and why it might not look how you expect.

[big note: I’m not a professional pundit. This is going to be less tightly woven than a data post. Probably treat this as a draft expression of views rather than a firm stance.]

What Is Moderation

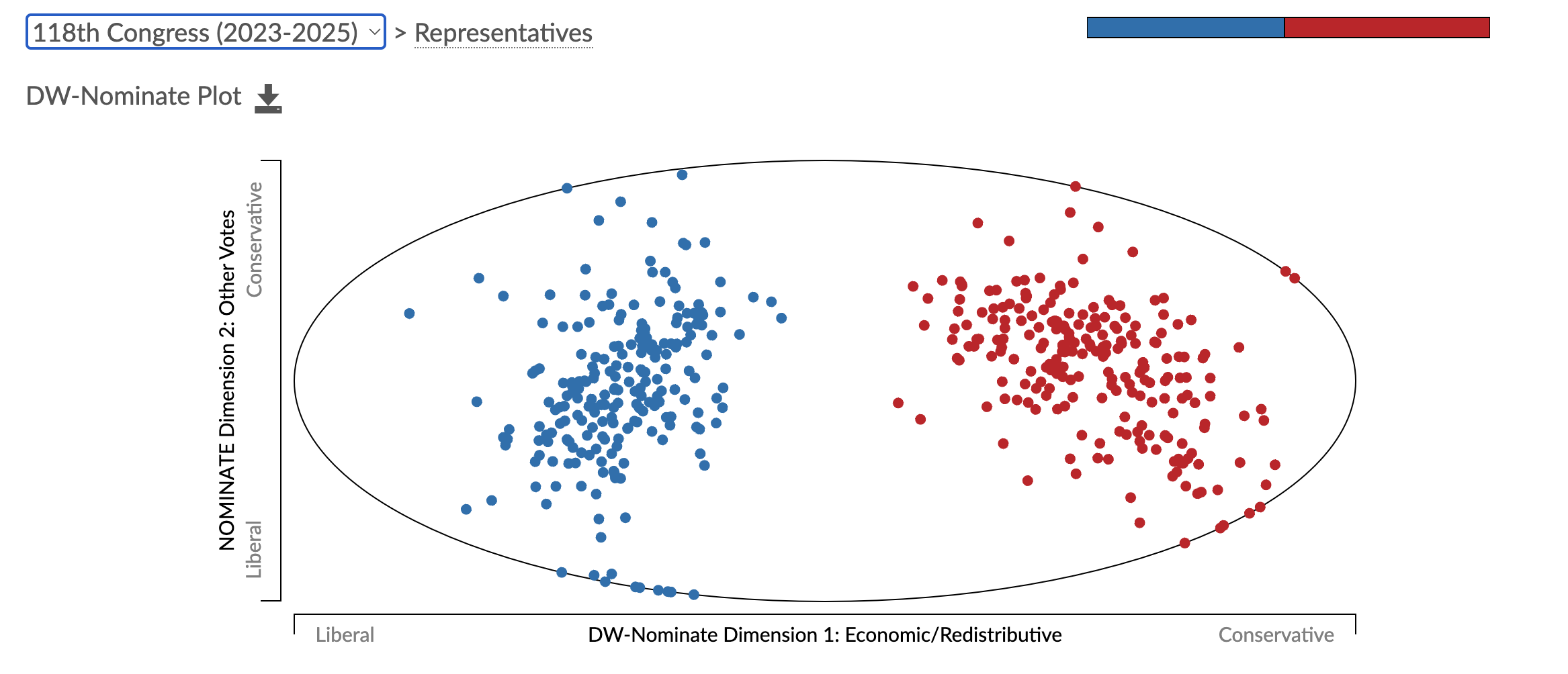

A very political science way to measure how liberal/moderate/conservative a politician is is to use NOMINATE, or the most common version cited, DW-NOMINATE. This uses roll call votes to map legislators on their voting patterns, collapsing these voting behaviors into two dimensions. This gives you the classic graph:

The big theory of NOMINATE is that all roll call voting behavior can be collapsed into two dimensions, one representing left-right alignment and one representing crosscutting issues of the day (social, race issues, etc). Recently, this second dimension has started to collapse, as congress passes fewer and fewer bills, leading to increasingly large must-past omnibuses and fewer roll calls where members feel able to defect.

Party Cohesion and the Demise of Meaningful Roll-Call Votes

One conclusion from DW-NOMINATE over the years has been increasing polarization and party cohesion, as you see fewer and fewer defections from party-line voting. I broadly agree with this line of scholarship but I think there’s a different conclusion for people more interested in what this means for maintaining a winning coalition:

As a random house member, you have less opportunity than ever to break from your party in ways that matter for policy outcomes.

Most of the bills where your vote matters are omnibus measures with a mix of priorities in them. This isn’t to say single-issue votes don’t occur- Jared Golden, for example, votes with republicans a lot on things like the “No Bailout For Sanctuary Cities Act”. That bill is currently sitting in the Senate Judiciary committee and shows no particular signs of movement.

The conclusion I draw from this is actually positive:

It doesn’t matter to Democratic policy priorities if some (or many) random house members break with us on issues, as long as they vote party line on big bills.

I find this kind of comforting- I really *do not care* what a frontline house member thinks about guns, or their position on the death penalty, or if they are skeptical of climate change. As long as they get on board with things like the IRA vote, we’re cool. It is vanishingly unlikely that their heterodox position will cause real policy change, and I am perfectly fine with giving them space to hold whatever mix of views speaks to them (and ideally, helps them win elections in their district).

How Does Moderation Happen

There’s two major ways you can instrumentally get moderation in a party.

All the members move towards the middle on all issues, staying cohesive but getting less left/right.

Each member moves towards the middle on a subset of issues, getting less cohesive and introducing a broader spread of issue positions.

The first option would happen if Democrats magically agreed to take a few steps right on everything, climate change, the border, social issues, crime, etc. This would be a fascinating degree of coordination in a party that, well....

The second option is to let individual politicians and candidates pick their own set of issues to move right (or left) on. In practice, this would render the median Democratic position more moderate, not require nearly as much coordination, and let candidates do what feels best for them and for their district.

The biggest barrier to the second option, in my opinion, is getting the national party, engaged Democrats, and national groups to chill the fuck out about it. Our elections are increasingly nationalized, and the pressure to fundraise elevates miscellaneous house candidates into the Twitter feeds of people who have never even been to their district. It’s tempting for candidates to take positions that are most appealing to online donors in order to boost their fundraising, or for people to elevate an odd position choice into a scandal of departure from orthodoxy. We should fund our candidates in important districts or who are trying to flip crucial house seats, but we should simultaneously really not care that much about the positions they take.

Let Candidates Be Weird

Back to Jared Golden again for a second, because he’s an easy example of moderation via heterodox position taking. He loves to take a R-leaning vote on random things, including “Denouncing the horrors of socialism”, “Condemning the use of elementary and secondary school facilities to provide shelter for aliens who are not admitted to the United States.” and the “Hands Off Our Home Appliances Act”.

Do these positions matter to him? Yeah, presumably, and they help him stake out a position as a more moderate Democrat. Should they matter to a Democrat not in his district? Probably not, since they have had ~0 impact on Democratic legislative priorities as a whole, and he’s not your representative.

The specifics of what issues they have unusual or Republican-style positions on is going to be down to each candidate. Maybe someone cares more about fish and less about guns, or feels really passionately about refrigerator over-regulation (okay, that one is from Golden as well). We should encourage potential candidates to feel out what’s going on in their district and embrace their own set of positions.

Beyond House Candidates

I started this with a focus on the House, because I think NOMINATE scores and roll call votes are usefully illustrative. But this sort of thinking goes double for non-federal candidates and politicians. Let them have weirdo, offbeat and even right wing positions on things that they are utterly unlikely to ever have influence over. It’s healthy to have a variety of opinions inside our big-tent Democratic party, and politicians have limited areas of influence. If the local dog catcher isn’t super sold on renewable energy, whatever. As long as they’re willing to do their jobs, and hold Democratic positions on things they have direct influence on, everything else is immaterial.

This is a step towards moderating, expanding our tent and freeing ourselves from the anxiety of worrying that our house back benchers have views we don’t agree with. It’s fine, their oddities are our party strength, and we can all be chill.